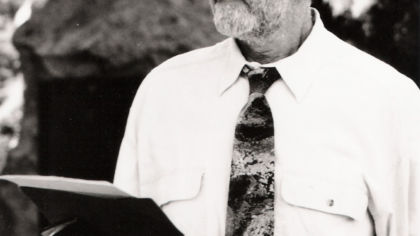

Harry Mazer

The Account of Lieutenant Ferguson’s Men

Harry Mazer, right flank gunner, 602nd Bomb Squadron, 398th Bombardment Group, 8th Air Force

As early as April 1942, the Allies tried to bomb and destroy the largest weapons manufacturing plant working for Hitler and his war machine in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia at that time – Škoda Pilsen. The overwhelming majority of attacks that took place during the next two years completely missed their target. The crushing blow came only at the very end of the war. To this day, there are debates about that last U.S. Air Force attack. Why did they launch an attack, when the American GIs were already fighting only 70 miles away, in Cheb (Eger)? One factor may have been the potential existence of the legendary German “National Redoubt” (“Alpenfestung” or “Alpine Fortress”). But, undoubtedly, the main reason was that the Škoda Works produced weapons – particularly cannons and tanks – right up until the end of the war, and no one had tried to stop them.

Following the communist coup in Czechoslovakia, in February 1948, the topic of the destruction of the armaments factory was frequently raised, in order to belittle the American military’s role in liberating western Bohemia. It was only possible to shed new light on this subject after the “Velvet Revolution,” in 1989, when assistance was undoubtedly provided by visitors with first-hand experience of these events – people whose renown extended beyond the borders of the region. One of these visitors, in particular, was Harry Mazer, the pilot of a bomber that fell victim to the city’s anti-aircraft defenses. The 602nd Bomb Squadron, of the 398th Bombardment Group, lost two aircraft during the “Mighty Eighth’s” attack on Pilsen on April 25, 1945. The 602nd Bomb Squadron, whose mission was to bomb the Bory Airfield in Pilsen, lost both Lieutenant Allen F. Ferguson’s Flying Fortress and also 1st pilot Paul A. Coville’s aircraft.

After his left wing was hit by flak, Ferguson´s airplane pulled to the left out of formation and started to go down. Shortly after that, the bomber went into a nosedive and, with pronounced trails of smoke streaming from engines 2 and 3, disappeared into the clouds. The radio message relayed from on-board the bomber, and intercepted by nearby aircraft, was indecipherable. Reports published later about the loss of the plane conjectured that the pilot had been hit.

Nearly fifty years later, Staff Sergeant Harry Mazer – right flank gunner and member of Ferguson’s crew – reminisced about the dramatic events of his last mission with the 8th Air Force: “In the somewhat less than a year that I had served with the crew, this was already our 26th flight. This time, the regular crew co-pilot, Johnny Schmid, didn’t fly with us because he had been shot over Germany two weeks earlier, when he was subbing for another crew. He remained in the Air Force after the war and went into retirement with the rank of lieutenant colonel. Harry Grey, our front gunner, also didn’t fly with us because he was laid up in the hospital with wounds he had suffered during the previous flight. We didn’t know that the raid over Pilsen would be the last mission of the Eighth Air Force.

What awaited us was a flight of ‘only’ eleven hours. We had no idea that the Allied command had issued a radio announcement, warning the Czechs of the upcoming raid. It certainly helped to fundamentally reduce the number of victims in the bombing but, at the same time, it allowed the Germans to get ready for us.

Due to poor visibility, we didn’t find the target during the first approach, so we were forced to repeat our approach. That’s when our aircraft was hit by German anti-aircraft artillery. Part of the right wing ripped off and, shrouded in fire, our burning bomber started to fall uncontrollably to the ground. I was able to jump out and, luckily, parachute down to the ground. The tail tower gunner, Sergeant William O’Maley, and radio controller, Sergeant Michael Brennan, jumped out after me. After we landed, the Luftwaffe detained me and O’Maley near the village of Litice. The Wehrmacht took Brennan into custody.”

During the final phase of the flight, Ferguson’s bomber circled once more around Litice, Lhota (near Dobřany), and Radobyčice, and then, while attempting to make an emergency landing, it apparently crashed into a field some yards away from the southwestern edge of Lhota. Right after that, a fire evidently broke out on board the bomber, destroying the front and center sections of the aircraft. Only the rear section of the fuselage, with the huge rudder, and part of the wings stayed together. The most recent sources of information give credence to the theory that the remaining five airmen from Ferguson’s crew were either killed in the crash or the subsequent explosion. Michael Brennan, who managed to jump out of the bomber before the crash, was detained and shot, either by a member of the local militia or a Wehrmacht soldier.

O’Maley and Mazer were lucky – when they landed on the ground with their parachutes, they were arrested and escorted on foot through Litice and the surrounding forest to the Bory airfield, which was burning. They spent the next 13 days under the watchful eye of a German guard, in the company of two airmen from another bomber group, whose Flying Fortress had been shot down, as well as a P-51 pilot who had been trying to escape though the Sudetenland and the Czech/Austrian border region. The end of the war found them in a Wehrmacht camp, somewhere between Linz and Salzburg.

Shortly after Czechoslovakia was liberated in May of 1945, an urban myth apparently sprung up in Litice about the murder of twelve American airmen, whom reports from that time said were found in “undignified graves near the village upon which the murderers of the Americans carried out ritual dances.” The often repeated claim that U.S. Headquarters in Plzen said there were twelve American airmen in the aircraft wasn’t accurate, however, because Ferguson’s crew had just eight members on that fateful day, and it can be proven that two of those survived. To complicate the research into the fate of Ferguson’s crew even further – a hand-written list of Allied casualties was slipped into the Litice municipal chronicles shortly after the war. In addition to the names of the five casualties from Ferguson’s crew, six unknown soldiers (allegedly Australians) are also listed. The last entry is the name of 1st Lieutenant Harold Cramer, the co-pilot of a B-17G bomber from the 447th Bomber Group that was shot down in a raid on Pirna, Germany, on April 19, 1945.

The memorial for Ferguson’s crew, which for many years bore the inscription: “In memory of the twelve American airmen killed by the Germans in Litice, in 1945”, was unveiled in Litice in July of 1946. When Harry Mazer visited Litice in 1994, he shared the following with those present: “Thank you to the residents of Litice and the Czech people for this memorial. Thank you for keeping this memory of our crew alive. On that tragic day, six young lives were lost. I know it is merely a drop in the ocean, compared to the bloodiest war in the history of mankind, but it has marked us and our families for our entire lives.”

During the past fifteen years, former members of the 398th Bombardment Group have been welcomed to Litice several times. On one of their visits to the original Litice memorial, they filled in the names of Allen Ferguson’s crewmen. They return to honor the memory of six young men who followed the call of their nation, crossed the ocean and, taking off from Britain (which had turned into one enormous airport during the course of the war), attacked a number of sites throughout Western Europe.

The raid on Pilsen, on April 25, 1945, was a turning point in the lives of many of the men from the “Mighty Eighth.” The war was finally over and they could return home. Their experiences from the period when they fought Hitler’s Third Reich were so intense, they decided to share them with others. The tragic April raid is described in one chapter of the book, “Hell from Heaven,” by Leonard Streitfeld, a bombardier with the 398th Bombardment Group. Harry Mazer also shared his memories of the ill-fated flight on the pages of his book, “The Last Mission.” Allen Ostrom, the long-term president of the “398th Bombardment Group Association of War Veterans,” and author of the book, “398th Bomb Group Remembrances,” has visited Pilsen and the Czech Republic numerous times. These books are not merely war veterans’ simple narratives – but, above all else, they embody a sense of righteousness and the fight against oppression and injustice.

From book 500 hours to victory