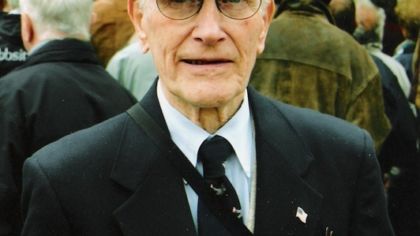

David C. Lustig

Last Over the Target

David C. Lustig, radio operator/gunner, 547th Bomb Squadron, 384th Bombardment Group, 8th Air Force

Forty-five long years after the ill-fated April bombing raid on the Pilsen Škoda Works, David C. Lustig, radio operator for the 384th Bombardment Group’s 547th Bomb Squadron during the war, visited Pilsen and the former Škoda Museum. David, one of the actual participants in the final “Flying Fortress” operation against targets in occupied Czechoslovakia, wrote about his final mission in gripping detail:

“As our sleepiness dissipated into the dank Grafton Underwood airfield predawn air in England, we funneled out of the darkness into the foreboding cigarette-smoke-filled briefing room. With the 384th Bomb Group crews sitting on the hard wooden benches in subdued apprehension, a beribboned briefing officer, pointer in hand, mounted the platform. Groans, louder than usual, rumbled through the room, as the parted curtain revealed the route across the ETo (evapotranspiration) map. That day’s mission markers pointed the way to Pilsen, Czechoslovakia. It was to be a nine to ten hour effort and the primary target was to be the Škoda Armament Works – to be bombed only on visual contact. When the weather officer predicted that the visibility over the target would be unlimited, the groans intensified.

This was to be my 22nd mission as a radio-operator/gunner with the 547th Bomb Squadron and my first with our Operations Officer, Captain McCartney. Our position was lead plane of the high squadron. Leaving the radio briefing with the code of the day and a flare bag, I climbed onto a truck tailgate for the cold dark ride to our hardstand. After a quick stop at the nearby armament shack, to pick up the left waist 50-cal gun barrel, I pulled myself through the waist door of our dimly lit B-17G. Our Fortress for this mission was an olive, drab, chin turretless, war-weary veteran of air battles past, but it was fine-tuned and ready for its task.

On this mission, I was to share the cramped radio compartment with ‘Mickey’ operator Flight Officer Eduards and his pathfinder bombing equipment. Personally, I never understood why Edwards was supposed to take part in the raid, since an order to bomb ‘only upon visual contact’ had been made. Despite this extra weight – the radar-jamming equipment and the usual 6,000 pounds of bombs – our four screaming Curtis Wrights pulled us up into the dark overcast sky before we ran out of runway. As we ‘mushed’ along, fighting for altitude, I fired a sequence of cartridges from the radio hatch flare gun. When we gained altitude, I looked at the two-colored flare that flickered above us, which I had shot out in order to identify our plane as the leader for the other eleven planes flying behind us. The bi-color flares arced brightly above us in the murky morning sky, beckoning the other eleven high element ‘forts’ (Fortresses) to assemble on our tail.

With the routine radio procedures accomplished, I attempted to relieve the tension by finding music or news to listen to on the BBC. To my astonishment, I was greeted by an announcement that, to me, was nerve-shattering – Radio Free Europe and the BBC had been carrying a specific forewarning from SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces), directly to the 40,000 Czech workers at Škoda, to: ‘Get out and stay out,’ because bombers were on their way to blast their factories – the first such raid of its kind in the war! I immediately shared this revelation with my nine other ‘lucky’ crew members. Their comments were unprintable.

P-51 fighter cover usually guaranteed we would arrive at the target area unhindered; however, it took little imagination to realize that giving enemy flak batteries plenty of advance notice made this bomb run prospect pretty grim. By now, the briefing admonition to ‘bomb the primary target visually only’ began to sink in: SHAEF was determined to spare Czech lives – even, apparently, at the expense of our own. At any rate, we were at 21,800 feet, on a near-perfect spring day, when we arrived over the initial point…

In what will always seem like too few minutes, black puffs of smoke wafted by my radio room windows and, simultaneously, the plane shook end-to-end from the ‘ka-woom – ka-woom’ of nearby concussions. Shrapnel began ricocheting off the thin aluminum skin like gravel off a tin roof and I compulsively hunched deeper inside my steel helmet and flak vest. The intensity of the flak was at an incredible pitch, when the interphone silence was broken by our bombardier’s: ‘Ten, nine, eight, seven, six…’ – it seemed interminable, ‘five, four, three, two, one…’ Then: ‘Take it around, Mac!,’ the bombardier yelled, and the pilot quickly banked sharply out of the tracking flak. My anticipated 22nd interphone report, ‘Bomb bay’s clear! Bomb bay’s clear!,’ was put on hold.

As our squadron made a wide sweep toward the initial point, an incredible picture filled my right window – hundreds of Forts, in tight formations – slowly, relentlessly being drawn toward a seemingly immense stationary murky area of deadly flak blasts. In one terrifying moment, that almost peaceful unreality was shattered when a B-17 broke up, trailing long tongues of orange flames and black smoke, as it tumbled out of the bowels of that tormented piece of sky. I stopped counting chutes as another Fort started down, belching a trail of black smoke. Only then did our precarious position become crystal clear. The desperation that I felt as we droned on toward our second assault has haunted me countless times since then.

The crescendo of the flak was increasing in that forty degree below zero hell. As I reached down and disconnected my heated flying suit cord – sweat was already cascading down my sides. I glanced at Edwards, hoping for a reassuring grin, but all I saw was a hunched-up figure under a flak helmet, his eyes glued to his scope. Our plane was bouncing with disconcerting regularity, from flak bursts just underneath, and the concussions and ricochets were intensifying. Suddenly, the interphone silence was shattered by the navigator yelling: ‘They’re tracking us, Mac! Take evasive action! Take evasive action!’ I’ll never forget Georgia-born Captain McCartney’s cool, drawling reply, ’Fisher’s got the plane, Schultz – Fisher’s got the plane!’ And so Captain Fisher had, as he calmly started his: ‘Ten, nine, eight…’

With my left forefinger on the camera switch, I pulled open the plywood door to the open bomb bay – the scene was unreal! Down below, the pastoral green, sun-drenched Czech landscape ‘drifted’ slowly beneath fleecy white clouds – with countless menacing shells bursting in-between. A ringing ‘twang’ interrupted the scene, as a large piece of shrapnel ricocheted off a 250-pounder in the bomb bay, causing me to momentarily slam the door shut. In retrospect, I’ve often laughed at the false sense of security I derived from that plywood door. Another large piece of shrapnel tore through the bulkhead and the plywood floor beneath my feet. Convinced that the flak batteries had our number, I snapped my chute pack beneath my flak vest and put my feet on the frequency meter under my desk. Fisher held the buffeted plane on its course, as he ran down the count: ‘Seven, six, five, four, three, two, one…’ And then, incredibly, ‘Take it around, Mac – take it around!’

An almost vertical right turn delivered us from the flak, as our well-perforated B-17 swung wide toward the initial point, for attempt number three. Light clouds over the target had obliterated Fisher’s view for a second time and, true to his orders, he wouldn’t jeopardize the civilian population.

Enervated and resigned to our fate, I watched the panorama of destruction, as we assembled at the initial point for our third time at bat in this debilitating ball game. Leader of the pack on the first assault, our squadron was now a ‘Tail-end Charlie’ – praying that the flak would run out before we did. No such luck! As the last remaining squadron in that forenoon sky, we were the targets of choice while running that blood-chilling third gauntlet to the hornet’s nest that was Škoda! Once again, the bomb bay doors opened, Fisher started his count, and the buffeting and battering commenced. It was do or die and we all knew it. Fuel reserves were low and getting home could be a problem. ‘Three, two, one – bombs away!’

Our prayers were answered! As the last of the twelve 250-pounders left the bomb bay, I hit the camera toggle switch, squeezed the interphone button with: ‘Bomb bay’s clear! Bomb bay’s clear!,’ and hung on while Captain McCartney maneuvered to evade the flak. ‘Bombardier to radio – bombed primary target – results very good!’ I quickly encoded the message, contacted our home base, and tapped out the news of our success.

Ten hours and fifteen minutes after takeoff we were being debriefed, exhausted – with oxygen mask marks still lining our faces. Our plane had sustained over fifty shrapnel holes. One shell, apparently a 37 mm, had bored completely through the right wing main I-beam without detonating – otherwise, this version of the mission to Škoda might not have been told.

To the best of my knowledge, this was the last 8th Air Force strategic strike of WWII… I probably transmitted the last 8th Air Force bomb strike message.”

From book 500 hours to victory