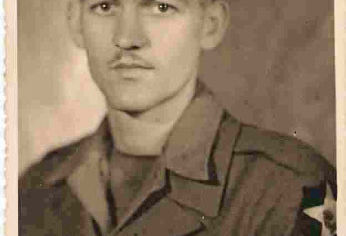

Glynn G. Raby

From Normandy to Pilsen

Glynn G. Raby, 2nd Infantry Division

On June 6, 1944, “D-Day” – the day that Allied forces stormed ashore on the Normandy coast to begin the invasion of mainland Europe, I was in a replacement camp in southern England. I had entered the U.S. Army in March, 1943, at the age of 18, and trained for over a year with the 106th Infantry Division in South Carolina, Tennessee, and Indiana. Thousands of us had been selected to become replacements for the men who had become casualties as the war progressed. That day, we were asked to donate blood, and most of us did, joking that we might get our own blood back.

Within a short period of time, I was in Normandy and joined “H” Company, 9th Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, near the town of St Lô. The fighting was difficult and progress was slow in the “hedgerow” countryside. Mounds of earth, up to 6 feet high with trees and shrubs growing on them, surrounded each field, providing excellent defense for the enemy. Finally, on about August 1st, our armor was able to start moving and rapidly attacked south, east, and west. While the main thrusts were to the east and south, our armored units also went west into Brittany, and the German troops withdrew into the larger towns and cities – mostly seaports. In mid-August, the 2nd Division moved west and joined with the 8th and 29th Divisions in capturing the port of Brest.

Outside the city, we found hedgerow countryside, similar to Normandy. Progress was again slow. I held the rank of Corporal and was assigned to assist our company communications sergeant. We laid telephone lines between our units and operated radios. When not moving forward, we always “dug in” – digging holes in the ground to climb into for some protection from shrapnel. One unforgettable day, we were being shelled and were in our holes. A direct hit from a mortar shell landed on Sgt. Thomas, perhaps 15 feet from me and he died almost instantly.

A day or two later, I had just completed a radio transmission to our Battalion Headquarters when someone called our code name, with what I thought was a German accent. My first thought was about “triangulation” – locating a radio by using three receivers and plotting beams to the transmitter on a map. Afraid that I might get a mortar shell dropped on me, I quickly turned the radio off and moved to another spot. I later learned that triangulation was not that effective and that mortars weren’t that accurate. The caller could have been an American with German ancestors, but I took no chances.

Another day, as I was on my knees digging in – with my entrenching tool raised to strike the ground, a small piece of shrapnel nicked my left thumb, drawing blood. A comrade suggested I go to the medical aid station to have it treated and get a Purple Heart Medal (for combat wounds). I refused, saying that if I did that, I would get hit between the eyes the next day.

The Old City of Brest was surrounded by a huge ancient wall – highly fortified by the Germans. We finally got inside and the enemy soon surrendered. By that time, it was late September – Paris had been liberated and the war had moved to the edge of Germany. We had a few days of rest, and I was able to visit a small town, Landerneau, where I found a bakery and bought a loaf of warm bread and some butter. It tasted so good, I ate it all.

Around October 1, we moved east – some by train and the rest of us in a motor convoy. We drove through Paris but didn’t stop. On October 4, after four days on the road, we entered Germany, about 10 miles east of St Vith, Belgium.

Our front lines in the Schnee Eifel Mountains included part of the famous Siegfried Line. Our company area had two “pillboxes” – the Command Post occupied one and the other was for supplies and our kitchen, where the cooks prepared food for us. Though a relatively quiet area, we did receive some artillery fire and a few enemy patrols, but not much. We were able to re-equip and rest a bit. Each week, a few men were given leave and visited Paris or England. We remained there just over two months until we were replaced by my old unit, the 106th Division, newly arrived from the United States.

We moved some 25 miles north and on December 13, began an attack at an important crossroads, Wahlerscheid, just inside Germany. The goal was to seize the dams on the Rur River before the Germans could breach them and flood large areas downstream. The crossroads was heavily defended with numerous pillboxes. The weather was bitterly cold and we suffered many casualties, both from enemy action and the brutal weather. The crossroads was captured the night of December 15, and the German offensive that would later become known as the Battle of the Bulge, began on the 16th. In danger of being surrounded, the Division commander had us pull back to the vicinity of Krinkelt – Rocherath – Elsenborn, Belgium, and halted the German advance there. On December 20, the commanding general of 1st Army sent a telegram to our Division commander: “WHAT THE 2ND INFANTRY DIVISION HAS DONE IN THE LAST FOUR DAYS WILL LIVE FOREVER IN THE HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY.”

Our defensive positions were along the Elsenborn Ridge and the Germans were able to advance no further in our area. In late January 1945, the German “bulge” had been erased and we resumed our attack to the east. Then we were able to see the tremendous damage our artillery and air power had inflicted: many dead bodies that the enemy had not been able to evacuate – frozen in the snow, and the untold number of tanks, other armored vehicles, and trucks that had been destroyed.

Each day, we advanced from daylight until after dark, crossing rivers and taking towns and villages, eliminating opposition when we encountered it. On February 11, we were in Bronsfeld and our company commander, Capt. Higgins, was killed by an artillery shell that hit the house he was in. Most of us respected him – highly.

A few days later, we moved into another town and expected to be there for a day or so. Our Platoon Sgt. and I went to a small house to determine if it was suitable shelter for some of our men. The sergeant directed me to check the cellar, while he checked the upstairs rooms. The cellar was dark, but I could see a stocking foot of someone lying just inside a doorway. I shook the foot, asking who he was and his reply in German startled me. I took cover and asked if anyone spoke English. One replied in English and I ordered that all come upstairs with hands up. I raced up, told the sergeant, and we went outside. In a few moments, seven German soldiers came up and gladly surrendered – they were weary of war and waiting for our arrival.

We reached the Rhine River about March 10 or 11. On March 21, we crossed the river in assault boats, a short distance south of the famous Ludendorf Bridge at Remagen. A few days later, I was given a week’s leave and a choice of several places to go, so I chose the city of Nice, on the French Riviera. A group of us were flown to Nice in U.S. Air Corps C-47 airplanes, equipped to carry paratroopers. In a first class hotel overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, we were housed two men to a room. Clean sheets, a private bathroom, meals in the hotel dining room with white tablecloths and napkins – we were served by the hotel dining room staff… We hadn’t enjoyed such luxury in many months. But the week passed much too quickly and we were flown back to the war…

It was early April and we were meeting very light resistance, so our forward progress became easier. We mounted tanks and other vehicles of the 9th Armored Division, stopping to deal with any opposition, and then resuming our attack. Our 23rd Infantry Regiment went into Leipzig and we continued east, to the Mulde River. It had been predetermined that we would halt there and that the Russians would halt at the Elbe River, some 20 miles to our east. Two great advancing armies meeting “head-on” would have been chaos.

On April 25, our regiment sent a large motorized patrol forward, in an attempt to meet the Russians. I was one of four men from H Company, 9th Infantry, in a Jeep with a mounted .30 caliber machine gun. We had a light tank, several other vehicles with mounted .50 and .30 caliber MGs, and a small observation plane overhead. Mid-afternoon, we encountered small arms fire coming from a town and returned fire. The bridges over a canal between us and the town had been destroyed, and we couldn’t go any further, so we returned to our unit back at the Mulde. That same day, a patrol from the 69th Division, just to our north, made contact with the Russians and made history.

On May 1st, the V Corps was transferred from the First Army to the Third Army, and we began a 200-mile motor march toward Czechoslovakia. On Jeeps, trucks, and tanks, we travelled part way on the Autobahn, with unseasonably cold weather and some snow. Near the Czech border, we dismounted and began an attack through the Sudetenland, where the pro-German residents were not glad to see us. On May 4th, the 11th Panzer Division surrendered and moved through our columns to the rear. Beyond the Sudetenland, the Czech people welcomed us with smiles, cheers, flowers, food, and drink.

As the war in Europe came to an end, some of the 2nd Division was in Pilsen, some units in several outlying towns. The 9th Infantry was in Rokycany, on the road to Prague. For about a month, the 2nd Division operated Prisoner of War camps and processed displaced persons. During this time, I received a promotion to Sergeant. Then we departed to return to the States for 30-days leave and to regroup and head to the war in the Pacific. While we were home on leave, the war in the Pacific ended and demobilization began. I was released on October 25, 1945 and returned home to resume studies at a college.

According to records provided by our 1st Sergeant, H Company had 166 men. As casualties occurred, replacements came to take their place (I was one of the earlier replacements). In the eleven months of combat, 38 men were killed, 123 wounded, and 107 hospitalized for various reasons. There were also 39 men wounded who remained on duty – that’s a total of 307 men who either died or were wounded. The phrase “Freedom is not free” is certainly true. The Czech people can also attest to this. How they endured the six years of Nazi occupation and persecution is beyond my imagination. My memory has faded, but I still have fond memories of the hospitality we received in Rokycany and Pilsen.

From book 500 hours to victory